Born to Thinning Ice

text and images by Jennifer Hayes

Jennifer Hayes is a National Geographic photographer, writer, and speaker who focuses on marine environments. She has documented aquatic systems from Africa to the Arctic and Antarctica, and is currently focused on the conservation of coral reefs.

Walking on sea ice, it is easy to forget that there is an ocean below you. The early morning sun bounces off a soft blanket of freshly fallen snow under an impossibly cerulean blue sky. The constant low hum of the wind carries a chorus of infant cries across this frozen world of white. I stand still for some time, listening and gazing across the landscape, absorbing the moment in its totality before pulling out my cameras. I catch a slight movement in a ridge of snow ahead of me, a gentle and clumsy wave of a tiny yellowish-white flipper. I shoulder my backpack and begin to wade slowly through the heavy drifts of snow.

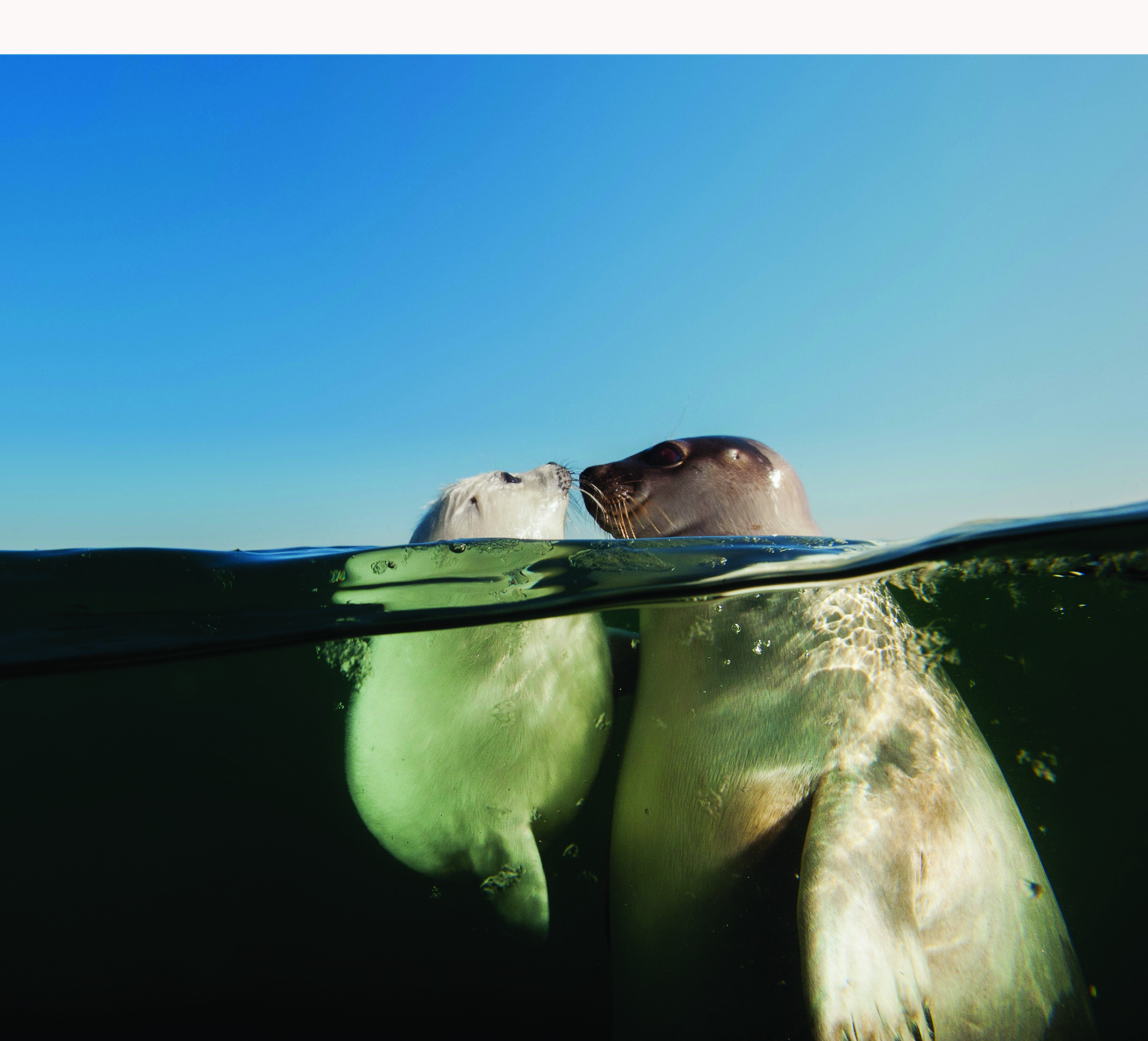

Sheltered from the wind in a small snow cave, it is a newborn harp seal, its white coat is still tinged with a soft hint of yellow from amniotic fluid. As it rolls over, I can see a thick pink placenta. Choosing a spot a polite distance away, I kneel in the snow, watching and waiting, making a mental note of the date: March 8, 2019. Moments later, I hear sloshing water and short grunting breaths. A whiskered face with big dark eyes rises from a nearby hole in the ice. After a quick survey of her surroundings, the female emerges from the water, using her long curved claws to pull herself up onto the ice and toward her pup. They meet with a nose-to-nose kiss of recognition that establishes kinship. She soon settles onto her side and closes her eyes as her pup begins to nurse.

With obsidian eyes, charcoal noses, and cloud-soft fur, the young seals are one the most charismatic creatures on the planet. And the tender scene I have just witnessed is playing out in a harp seal nursery near the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Québec, one of three northwest Atlantic harp whelping grounds.

In late winter, pregnant females migrate here from the Arctic in search of a suitable platform of sea ice upon which to birth their young. Males tag along, eager to mate. The pups are born on the ice in late February and early March, weighing some 11 kilos at birth. Their mothers will nurse them for a fortnight, during which pups grow plump, gaining 2-plus kilos a day. This fat reserve will prove critical to their survival once their mothers leave them to mate again before migrating back into Arctic waters. The fledging pups must learn how to swim and feed and fend for themselves. If they can survive this critical and challenging phase of their lives, they can expect to live 25 to 35 years.

Scanning the ice, I see larger, more active pups in their whitecoat phase. Born days earlier, these pups have the distinct advantage of time on their side in the increasingly unpredictable world of weather and its impact on the ice beneath them.

Late-born pups, like the one I have just witnessed with its mother, will need adequate time and sufficiently durable ice to survive in a world where spring comes earlier every year and, with it, increasingly strong storms that demolish the ice pack in an instant. A life born to ice is difficult and pup mortality can be high, especially in a season with higher-than-normal temperatures and an attendant reduction in sea ice. That “deadly combination” is an ever-increasing reality for the Gulf of St. Lawrence harp seal herd.

Ice conditions in 2010, 2011, 2016, and 2017 were unsuitable for pup survival, and mortality during these years exceeded 90 percent. If this temperature trend continues, there is a distinct possibility that the Gulf whelping ground will diminish to a point of local extirpation. To survive, the seals must follow the ice wherever that may be, forcing them to establish more northerly whelping grounds than in times past.

a chance encounter and

a passion for harp seals ignited

I made my first trip to the Magdalen Islands—an archipelago that resembles a slew of ships at anchor—in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2011, on a National Geographic assignment with my fellow photographer and partner, David Doubilet. Our goal was to document the Gulf of St. Lawrence’s marine ecosystem, an assignment that would introduce us to an intriguing cast of characters, including scientists, fishery managers, fisherman, and Mario Cyr, our guide for the harp seals of the Magdalen Islands.

Our research platform was the Jean Mathieu, an ice-worthy fishing and harp- seal-hunting vessel. While the Magdalen Islanders have hunted harp seals here since the 1600s, the great historic hunts that ranged into a few hundred thousand seals are a thing of the past today, with current hunting seasons rarely topping 50,000, and the hunts are driven more by a nostalgic link to tradition than by market demand. When ice conditions are favorable, some seals are still taken for personal use, restaurants, medical research, and what remains of a limited Canadian commercial market. Proportionally, larger numbers of seals are hunted on “the Front,” the belt of sea ice off Newfoundland and Labrador.

When we boarded the boat, I could sense that the crew was wary of us, and as journalists, we were equally wary of hunters. But perceived tensions quickly dissolved when we shook hands and talked. Trust is priceless. Direct communication is as key in storytelling and journalism as it is in any business interaction. As they would learn, our story coverage was not to be about the hunt, but about the more ominous and chronic threat of climate change and the changing life on thinning ice. We would need their expertise and help to accurately tell that story.

Pushed by wind and current, the ice pack was a moving target. Forty hours would pass before the captain nosed the boat into a patch of sea ice supporting a herd of 10,000 or more seals. We drifted with the ice day and night. It is extraordinary to pull on crampons and walk among this pulse of life on the ice and then to put on a dry suit, mask, fins, and snorkel and slide into their world with a camera.

Life at the edge of the ice can be a busy place, with mothers coming and going beneath a dark blue cathedral of ice pierced by shafts of light; apprehensive whitecoats peering into the sea, considering their first swim; or veterans splashing about, exploring what it is to be a harp seal.

Despite the rush and challenge of finding the herd, the assignment was a photographic success that would gift me a life-changing moment. I am a born skeptic of tales about human–wildlife interactions, especially ones in which creatures of other kinds come to our rescue.

On our last day in the ice, I was photographing a mother and her pup swimming in brash ice, when a male seal nipped at my ankles and then scrabbled up and over my back, pushing me beneath the surface and dislodging my mask. As I duck-dived for the sinking mask, I felt a swell of water as the mother harp seal swam down past me, battling off the testosterone-charged male. She surfaced slowly and swam 360 degrees around her pup. Once satisfied her pup was safe she used her head and body to gently nudge and guide both the pup and I through the water toward the safety of solid ice.

I was still processing what happened as we got underway, heading back to port ahead of a building low-pressure system. The storm tore across the Gulf, whipping it to froth and frenzy. By the time we made shore we learned the sea ice had disintegrated beneath the herd and all the pups had died. It was a perfect recipe for catastrophic loss. Higher than normal temperatures produced enough ice to attract the pregnant females who gave birth on the unstable platform. Powerful storms turned the Gulf into a tempest. That year’s class of harp seals was lost to the sea.

Following the publication of our National Geographic story, “The Generous Gulf,” in 2014, our commitment did not end on the pages of the magazine. The storm made my encounter bittersweet and made me realize that we are now facing a new truth: the world of ice is only as a solid as a dream. This harsh realization has galvanized my resolve to return each year to keep a pulse on harp seal lives on thinning ice and to connect others to these creatures and the plight of their melting world.

Charting a future for harp seals in

an age of warming seas

If there is a silver lining to this story it is this: the decline in the market for seal pelts has opened a wider door to boat-based and helicopter ecotourism, providing an alternative income to hunting.

Ecotourism has been instrumental in enabling ordinary citizens to engage with the natural world. And as we know, engagement often leads to action. And so it was during my trip to the Magdalen Islands this past spring that I had a chance to witness such engagement firsthand.

I had planned to make my annual pilgrimage to the harp seal nursery when Mario Cyr called to tell me that he would be canceling our boat charter. All of the fishing boats, he said, were “iced in.” While the cancellation clearly would call for a change of my expedition plans, disappointment was immediately displaced by delight. For I knew it was going to be a very good sea-ice year for the harp seal.

With a need for a workaround, the situation presented the perfect opportunity for me to experience helicopter-based harp seal ecotourism. The local tour company at Château Madelinot was operating with three helicopters, the sea ice was solid, and seals were finding stable birthing grounds close to the islands.

I booked a flight from Québec City and made arrangements to share a helicopter ride with National Geographic filmmaker Bertie Gregory.

It was extraordinary to visit the nursery with ecotourists for the first time. I watched a teenage girl sitting quietly next to a plump whitecoat that gazed intently back at her, a tear collecting in the corner of her eye. I met couples on a belated Valentine’s Day date, a single doctor, families with kids, a recent divorcée, and a cancer patient. I was inspired by Rei Ohara, a photographer and Japanese guide, who was celebrating his thirtieth year with the seals; a young lady who brought along a stuffed seal from childhood; and a twenty-something young man named Alexander from Kingston, Ontario, who had slept in his car, having spent his last dollar on the last helicopter ride out to the ice that season.

Passion and curiosity had brought them all here to learn, to heal, to grow, and to connect with a charismatic animal whose fate and future is so intimately connected to the ice beneath it, and more important, to the impact of our behavioral choices as humans. For me, the experience was nothing short of enlightenment.

I do not know what the coming whelping season will bring: solid sea ice, weak ice, or no ice. No ice is far better than weak ice. When there is no ice, the pregnant female seals, desperate for a birthing platform, will exit the Gulf and search for better ice on the Front. Weak ice, on the other hand, seduces the females to stay and birth their pups on unstable ice that is likely to collapse before the

pups mature.

Although January ice charts did not portend a good year, the February temperatures dropped significantly. Sea ice has since formed in the Gulf, and the herd has gathered on it. The first pups were observed on February 23. In the weeks that follow, we will learn the fate of the 2020 class of harp seal pups. As of this writing, I am on my way back to the ice nursery to continue to document the story of the harp seal as it unfolds in the face of climate change.